Or “How to keep your sanity while being an app publisher”

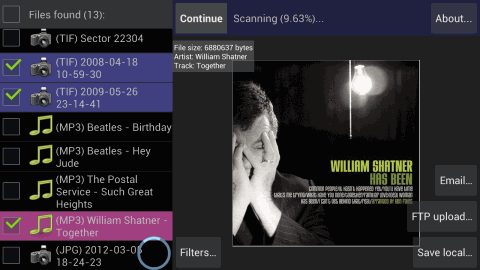

It has been roughly a year since I’ve published my first significant Android app (DiskDigger), and roughly a month since I’ve published my first paid app (DiskDigger Pro). Over the course of this time, I’ve learned some valuable lessons about human nature, specifically about the nature of the humans that leave star-ratings and write reviews about your app. If you’re a fellow app developer, I hope you’ll commiserate with this post. And if you’re a newcomer to the Google Play Store ecosystem (or the Apple App Store, for that matter), take heart.

Of course, this article assumes that your app actually works, and does what it promises. It assumes that negative reviews are not expected for your app, and come as a surprise to you.

People Will Be People

We’re all familiar with YouTube comments, and the breathtaking stupidity to which the commenters are guaranteed to stoop. Most of this idiocy comes from the fact that the commenters are able to write anonymously (or at least semi-anonymously), which is enough to open the floodgates of ignorance, hatred, bigotry, trolling, and everything else. Much of this mentality translates right over to app reviews.

If you’re an app developer, you will get bad reviews. Get used to it. This is for a very simple reason: there’s a significant imbalance in the activation threshold for writing a good review versus a poor review. In order for someone to give your app a five-star rating, and a good review, they have to be extremely impressed by it. However, in order for someone to give a one-star rating, they only have to find a single wrong thing in the app! Maybe it’s some portion of the interface they find annoying, or some behavior they didn’t expect, etc.

This is fairly similar to reviews of restaurants that we find on Yelp. Most of the positive reviews on Yelp come from people who write reviews as a hobby (who make it a point to write reviews of every place they visit), whereas the negative reviews are from people who happen to catch the wait staff having an off day, and write a review on Yelp when they otherwise wouldn’t.

You Can’t Please Everybody

If you worry about pleasing all of your users, you will burn out. For one thing, if you try implementing everyone’s feature requests, your app will become a disjointed mess, and will likely be used by fewer people than before. Choose very carefully which feature requests to implement, and acknowledge that certain users simply cannot be helped by your app, even if their poor review is constructive.

And another thing: if you try implementing everyone’s feature requests, you will develop feelings of resentment towards your users when they continue to give poor ratings (which they will, for the reasons stated above). You will say, “How dare you rate my app poorly, when I’ve spent so much time implementing features that others have asked for!” These kinds of emotions are highly destructive, and pave the way towards madness.

Don’t Expect Them to Read Instructions

Asking your users to read any kind of instructions prior to using your app is asking too much. Case in point: My DiskDigger app only works with rooted devices. I state this in the app description several times, and very plainly. I also put the word “root” in the title of the app. And yet, there have still been people who wrote a review to the effect of, “When I launch the app, it says I need a rooted device. Why wasn’t I warned about this?” No, I’m not joking. Read the reviews for yourself, if you like.

If your app requires the user to have any kind of a priori information before using the app, be prepared to receive poor ratings from users who weren’t aware of it.

Other Oddities

Some people seem to think that giving a one-star rating is a good way of asking for help. I have received numerous one-star ratings where the user says, “Can someone help root my phone?” or, “Can you implement feature X?” I’m not sure how to deal with such “reviews,” except to shrug my shoulders and move on, since the sight of the one star is enough of a turn-off to not want to help this person to begin with. Also, while it’s possible for them to change their rating after they’ve been helped, the time-to-reward ratio is really not worth it. They’re always welcome to contact me directly, anyway.

On the flip side, other people have written five-star reviews in order to come to my defense against the one-star ratings. While I certainly appreciate these kinds of sentiments (since they balance out the trolls somewhat), I would rather get uniformly honest reviews of the software itself, rather than meta-bickering in the comments.

Responding to Reviews

The Google Play Store allows developers to respond to each review. However, the current mechanism for doing this is deeply flawed, because the responses are posted publicly, underneath each of the reviews!

Furthermore, the responses are limited to 350 characters! This is hardly ever sufficient to thoroughly answer the user’s questions, or guide them towards resolving their issues.

All of this creates a hostile environment, where the developer is encouraged to come down to the same level as the reviewers. That’s not to say that the reviewers aren’t smart, or don’t have legitimate issues or concerns. It simply encourages the developer to become defensive, or even argumentative, towards the users. It’s almost as if Google is saying, “Hey, look what this guy wrote about your app! Are you gonna let him get away with that? Use these 350 characters to stand up for yourself!”

Lastly, the very notion of “responding to reviews” encourages the developer to constantly check the reviews. For a developer who is prone to OCD (like myself), this kind of thing can be very hazardous to one’s mental health! Even now, a part of myself is desperate to log on to my Play Store console, and check for any new activity.

Suggestions to Google

Here are a couple suggestions that would improve the Play Store experience for users, as well as for developers:

Before allowing a user to write a review, ask if the user wants to contact the developer for support! It’s baffling why Google doesn’t display contact and support information for each app much more prominently than it currently does.

If the user selects anything less than five stars, make a text box that slides out and says, “Having issues or any questions regarding this app? Ask the developer for help!”

If that’s too much to ask, then at least allow developers to respond to reviews privately, and directly over email. Responding privately instantly changes the dynamic of the conversation. It also consolidates the number of support venues that the developer has to worry about, since the issue has been moved to email, which should be the primary support venue.

And if that’s too much to ask, then at least notify developers when the user has read the response, as well as when the user updates or amends the rating to which you replied.

Like Water Off a Duck’s Back

Let’s compare app reviews to restaurant reviews one more time. There are several key differences between the two.

A successful, established restaurant might get, say, five reviews on Yelp per week, at the most. Therefore, the manager of the restaurant might do well to read each review (and will have time to do so), to see things like which menu items are trending and which ones aren’t, how the service staff is performing, and so on.

However, a successful app can get dozens of reviews per day. It’s therefore completely impractical for the developer to pay attention to each one. At this point in the app’s lifecycle, it’s more useful to look at the trends of your star-rating (e.g. on a weekly basis). If the rating takes a dive shortly after you publish an update, it might indicate that the update contains a bug, and merits further investigation. (If the app really does contain a bug, you’ll receive messages from users via email, anyway.)

There’s one more crucial difference between app reviews and restaurant reviews. Restaurant reviews are generally written by intelligent adults with a discerning palate. App reviews, however, can be written by anyone in the world, including 13-year-old trolls, 90-year-old senile grandparents, and everyone in between.

If you haven’t guessed this by now, the proper way to deal with negative reviews is to simply let them roll off you, like water off a duck’s back. Most importantly, don’t let them get to you: don’t let them affect your work or break your spirit. They will always be there; get over it.

Whether or not you make money from writing software, it should at least make you happy. If you find that it isn’t, then you’re doing it wrong. The fact that a single other person wants to use your software should be reward enough. The fact that your app gets occasional negative reviews simply means that your app has reached that level of popularity, and that’s something to celebrate, not fret over.