So I’ve been rewatching Star Trek: Voyager recently, and thought I’d share some notes and observations. As a disclaimer, I had the show running mostly in the background, so I didn’t pay particularly close attention. Nevertheless, this re-viewing has pretty much solidified my conclusion that this series is my least favorite in the franchise. Let’s begin.

Captain Janeway

Oh, Captain Janeway…. I don’t think I agreed with a single command decision that she makes, starting with the very first episode where she decides to strand her crew in the Delta quadrant, and ending with the very last episode where she decides to travel back in time to help Voyager reach the Alpha quadrant sooner (because of how much she regrets her decision to stay in the Delta quadrant).

The complete, repeated disregard for the prime directive (including the Temporal prime directive) has me questioning her fitness for command.

At least she ends up where she belongs — in a women’s prison mashing potatoes for other inmates. #lockherup

Neelix

The Jar-Jar Binks of the Star Trek universe! It’s hard to believe he survived that long before coming aboard Voyager without being blown to bits by… pretty much anyone who encountered him. And it’s also hard to believe he wasn’t killed off in any number of ways during Voyager’s seven-year journey. Being strangled by Tuvok would have been a satisfying outcome, and this actually happens, but only as part of a holodeck simulation. It’s as if the writers are fully aware of how annoying this character is, but just want to stick it to the audience.

Stupid and/or tedious enemies

The Kazon. We’ve seen all of this before. Generic humanoids with a prosthetic forehead and a bone to pick. No wonder Seska (a secret Cardassian) fits so well with the Kazon when she defects to them from Voyager — they are nearly identical species, except that the Kazon are much stupider and less cunning. How did they ever invent warp travel? In fact, the Kazon, the Ocampa, and the Caretaker can be very closely compared with the Cardassian / Bajoran / Prophets trifecta of Deep Space Nine, except the latter were explored much more deeply and meaningfully.

The Hirogen. We’ve seen this before, too: one-dimensional enemies that are given a single human characteristic that’s exaggerated to absurdity. Basically a blend of Klingons and Jem’Hadar, they are obsessed with “hunting” and “prey,” and made for some woefully tedious and predictable episodes.

On the other hand, there were some great enemies too, such as Species 8472, which deserved many more episodes than they got. The interplay between Voyager and Species 8472 became really nuanced, and I was looking forward to more stories with them involved, but it didn’t happen.

Notable cameos

One of the truly enjoyable things about re-watching this series was the cameos, some of which I hadn’t even realized until now. Imagine watching a random episode and thinking, “Hold on, isn’t that… Scott Thompson?!” Why yes, it is — he makes a guest appearance in the episode Someone to Watch Over Me, and is delightful as always.

Other welcome appearances include Jason Alexander, who plays the leader of the “brain trust” in the episode Think Tank. I kept chuckling whenever he spoke. And of course there’s Sarah Silverman, an up-and-coming comedian at the time, who plays the nerdy-but-sexy SETI researcher in Future’s End.

Time travel as filler

A noticeable fraction of the episodes are time travel stories where most of the episode happens in an alternate timeline which, by the end of the episode, resets to the beginning without the crew knowing that anything happened. This makes the episode completely pointless, unless it’s redeemed by some meaningful character development, which it generally isn’t. Here are just a few such episodes that I can recall:

- Time and Again, in which the Voyager crew detect a planet that has undergone a catastrophe, but it turns out that the crew themselves are the ones who cause the catastrophe in the future. Once they manage to prevent it from happening, the timeline resets to the beginning, with all the events of the episode never having taken place.

- Timeless, in which, fifteen years in the future, Chakotay and Harry Kim correct a mistake that happened fifteen years prior, which had caused the destruction of Voyager and the rest of the crew. Once the mistake is corrected, the timeline is reset, with the events of the episode never having taken place.

- Year of Hell (a two-parter), in which the crew is faced with a species that is bent on tampering with the timeline in order to become the most prosperous and dominant species in the sector. They do this using a ship that can fire a “temporal incursion” beam that erases any object from ever having existed. When Voyager finally manages to destroy the temporal incursion ship (without any help from the 29th Century time police, who should have been there, right?), the timeline is reset, with the events of the episode never having taken place. Note: this episode had a huge redeeming factor in the form of Kurtwood Smith, whose performance made the episode more watchable than most.

- Relativity, in which a renegade captain from the 29th century is obsessed with destroying Voyager because he’s fed up with all the trouble they’ve caused with their time traveling (I know how he feels!). Once this captain is apprehended, the timeline is restored, with the events of the episode never having taken place.

I’m fairly certain there are a few more that I didn’t mention, but you get the idea. It feels like the writers would too often fall back on the “alternate timeline” / “it was all a dream” trope, rather than explore more meaningful ways to advance the story or develop the characters.

“Science”

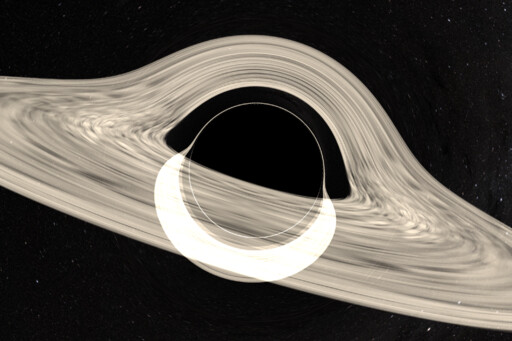

What good would a dissection of a Star Trek series be without a few nitpicks of the science and technobabble that they use? The science explored in Voyager is laughably terrible, as it often is in Star Trek, but fortunately it’s laughable in a good way. As in, it’s so absurd that it overflows into being humorous.

Remember when Voyager gets stuck inside the event horizon of a singularity (in the episode Parallax) and pokes a hole through it using warp particles? And when Neelix mansplains the event horizon to Kes with utter nonsense? Oh man, that’s the good stuff.

Perhaps the most absurd episode, to the point where I felt stupider after watching it, was Threshold, which is the one where Tom Paris builds a shuttlecraft that can achieve Warp 10, which is “infinite speed.” Mind you, the scientists and theorists at the Daystrom Institute have spent centuries refining warp technology to attain this goal without success, but Tom Paris (a random-ass pilot without any scientific background) does it in a few days.

The crew acknowledges that this is an impossibility (since traveling at infinite speed would mean occupying all points in the universe simultaneously), but Tom does it anyway! Of course, after attaining Warp 10, Tom starts to experience some changes: he abducts captain Janeway to a distant planet, where they de-evolve into giant salamanders, and have salamander babies. But don’t worry, the crew finds them soon enough, and the Doctor restores them to human form, with all their memories and skills intact. What happened to the salamander babies, which are now the most unique species in the entire universe? Ehh, who cares. (Whoops, spoilers!)

Verdict

A few memorable episodes, some pretty good performances (especially by Robert Picardo as the Doctor), but the premise and overall dullness and repetitiveness of the episodes makes it more suited for running in the background rather than the foreground.