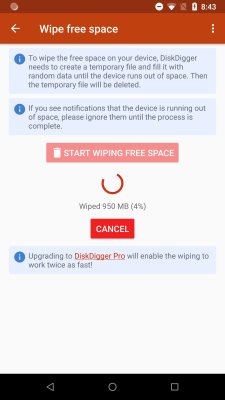

A while ago I introduced a feature into DiskDigger which wipes the free space on your Android device. This is useful for ensuring that no further data could be recovered from the device, even using tools like DiskDigger.

A while ago I introduced a feature into DiskDigger which wipes the free space on your Android device. This is useful for ensuring that no further data could be recovered from the device, even using tools like DiskDigger.

However, some users have been reporting that the wipe feature doesn’t seem to be working properly: certain bits of data still seem to be recoverable even after wiping free space. This is partially my fault for not sufficiently clarifying how to use the feature most effectively, and partially Android’s fault for making its storage and security system exceedingly complex.

Let me clarify a few things about how this feature works, and emphasize some precautions you should take before proceeding with the wiping.

- In order for the wipe to work correctly, the files that you need to get wiped must be deleted from the filesystem. The wipe can only cover the free (unallocated) space on the device’s storage. If the files still “exist” in the filesystem, they will not be wiped.

- In addition to deleting files you would like to be wiped, recall that many apps maintain a local cache of data that the app deems necessary to store. This could include things like thumbnails of photos (or even full-resolution copies of photos), draft copies of documents, logs of conversations and activity, etc. To delete all of these things, you would need to go to Settings -> Apps, and for each app, go into “Storage” and tap “Clear cache.”

- Even worse, some apps break the rules and store data outside of their designated cache folder. Therefore you may even need to tap the “Clear storage” button for each app, instead of just “Clear cache,” or even use a file-manager app to navigate your device’s internal storage and manually delete unwanted files, and only afterwards go back to DiskDigger and wipe free space.

Of course the best way to make sure the data on your device is no longer recoverable is to perform a factory reset of the device, and then use DiskDigger to wipe the free space. But even then, certain portions of the data could be recoverable, depending on the manufacturer’s definition of “factory reset,” or how the given version of Android handles resetting.

All of this is to say, there is unfortunately no single guaranteed fool-proof way to permanently wipe your Android device, but DiskDigger’s “Wipe free space” function goes a long way if used properly.