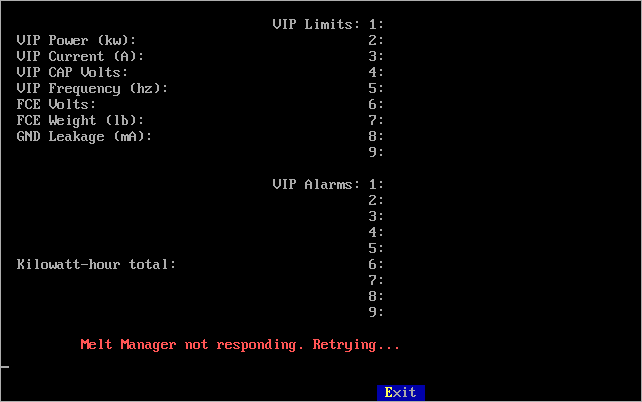

I am now a staunch advocate for ECC RAM, after the events of last week. You see, over the last several weeks my main desktop workstation has been misbehaving, with occasional freezing and crashing. After some diagnostics I began to suspect a faulty RAM module, and sure enough, upon performing a quick run of memtest86, it lit up the screen with a multitude of bit flip errors, at numerous memory locations, indicating that something was seriously wrong with the RAM.

Within a day or two I scrambled to replace the RAM modules with new ones, and when this was done the problems resolved themselves and everything was stable again. However, there was another more sinister side effect that I discovered shortly afterwards: Some of my data was corrupted! That’s right, it was the worst-case scenario for RAM failure: bit flip errors that get written back to the disk. I discovered that several video files that I had been editing had corrupted bits, and were no longer usable. Fortunately I still have the original source materials for the videos which I can use to recreate the final videos. It’s an unfortunate waste of time, but it could have been a lot worse if I’d let the RAM failure go on even longer. There doesn’t seem to be any further corruption in any more of my personal data, and just to be on the safe side I performed a clean install of Windows, to ensure that no system files or program files are corrupted.

The point of the story is that the data corruption was completely preventable, if only my RAM had ECC built into it. But because it doesn’t, these kinds of bit flip events go completely undetected, and proceed to wreak havoc on the integrity of our data, right under our noses.

Memory manufacturers assure us that desktop RAM is so reliable that it doesn’t need ECC, that the probability of bit flip events is so low that it’s not worth the extra “cost” of ECC. Chip manufacturers (i.e. Intel) produce CPUs that don’t even support ECC memory. Users are expected to upgrade to server-grade components just to get access to ECC memory.

Let’s quickly review the reasons why server-class machines are deemed to be “deserving” of ECC memory, while desktop machines are not:

On a personal desktop computer, your data is stored permanently on a disk, whether it’s a spinning hard drive, SSD drive, memory card, and so on. When you want to do something with your data (e.g. write a document, edit a photo, etc), the data is loaded into RAM, and when you’re finished modifying your data, it’s written back to the disk.

On a server machine, however, the situation is different: since disk access is much slower than RAM access, the server must keep as much data as possible in RAM, so that the data is instantly available to clients who request it. This means that the data ends up sitting in RAM for extended periods of time. If the RAM were to experience bit-flip errors that went undetected, the server would serve incorrect data, or worse, would end up writing incorrect data back to the disk. Therefore, the server’s RAM has ECC, so that it will correct itself in case of an occasional bit flip.

This is oversimplifying a bit, but the difference between a server and a desktop, for this exercise, is simply the amount of time that data is made to sit in RAM. So then, are we supposed to accept that if our data doesn’t remain in RAM for very long, it doesn’t need ECC at all?!

By the way, you’d better believe that your disk(s) have all kinds of error correction schemes built into them, which work automatically and transparently. It’s completely normal for data written to a physical medium to be imperfect, and those imperfections will be corrected by the firmware of the disk.

Well guess what? RAM is a physical medium, and yet we’re simply asked to take the manufacturers’ word that our RAM is reliable enough to never need ECC for the use cases of a desktop workstation. Well, I’m here to say that these practices are reckless, and represent a ticking time bomb for anyone who uses non-ECC memory for anything nontrivial. And it seems I’m not the only one.

(discussion on HackerNews)